Roam home to a dome

Where Georgian and Gothic once stood;

Now chemical bonds

Alone guard our blondes

And even the plumbing looks good.

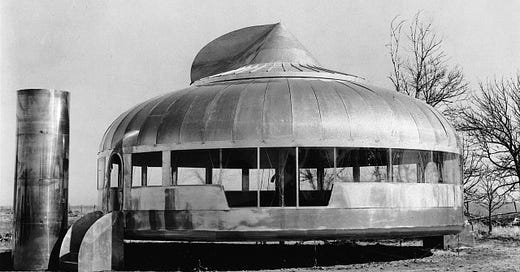

So sang Richard Buckminster Fuller, the eccentric American designer and theorist, in praise of his “Dymaxion House.” This lightweight dwelling, which was indeed dome-shaped, could be made in a factory, shipped in a tube and assembled in less than a day. Raised off the ground by a concrete pillar, it looked like a big metal pumpkin, and somehow contained living space, bedrooms, bathrooms, and a kitchen fitted with the latest appliances. Buckminster Fuller was convinced that modern people ought to live in such mass-produced structures. He first designed one in 1927, and almost persuaded the Beech Aircraft Corporation to start manufacturing them in the 1940s.

Partly through Buckminster Fuller’s influence, the house as prefabricated pod became fashionable in the mid-twentieth century. In Britain, it made an appearance in the Smithsons’ “Home of the Future,” exhibited in 1956, and in the provocative schemes of the Archigram group and the Japanese Metabollists during the following decade. Today, however, prefab homes are no longer a subject of futuristic speculation, and nor do they look like something that belongs in space. Various forms of modular construction (as prefab is formally known) are part of the housing mix in Sweden, Japan and Germany. In a new essay for Unherd, I look at how the industry is faring here in the UK. After visiting two developments in Bristol, my sense is that prefab still has a long way to go, but should not be ruled out as part of the response to Britain’s housing shortages.

What I find most interesting about prefab is that it reveals the peculiar way we think about houses in comparison with other artefacts. Its supporters point out that factory production has allowed all kinds of engineered products, from cars to electronics, to become much more sophisticated and also much less expensive. So why do we insist on building houses the old-fashioned way? The question seems especially pertinent in the UK, which has a shrinking, ageing construction workforce and a reputation for shoddy new-builds.

There are practical reasons why houses are more resistant to factory methods, but it’s also the case many of us are uncomfortable with the idea of a home coming off a production line. We think of mass-produced goods as identical, economical and short-lived, whereas the ideal house – at least for the typical middle-class European – tends to be unique, characterful and long lasting. To my mind, there is something depressing about a home that comes into being through a process similar to IKEA flat-pack assembly. If you browse AirBnB reviews, or the marketing materials of estate agents, you will find that notions of charm and prestige attach themselves most readily to structures that show a connection to the past.

It’s easy to come up with a materialist explanation for this, relating to the status of houses as financial assets. When Chinese president Xi Jinping warned his subjects that “houses are for living in, not speculation,” he was invoking a state of affairs that already exists in many parts of the developed world. Scarcity has allowed homes to become a common means of accruing capital; something you save and borrow large amounts of money for, view as an investment, and pass on to your children. As such, it’s not surprising that we regard them as inherently valuable, lasting things, rather than goods to be “consumed.” This may explain why Japan is such an outlier in its attitudes to housing. For various historical reasons (such as a proliferation of temporary structures after the Second World War, and frequently updated building codes), Japanese dwellings are expected to lose value as they age, rather like cars. Consequently, they are designed to last for a couple of decades before being knocked-down and replaced with something better. This is one place where a home does resemble a consumer product, which probably accounts for the relative success of modular housing there.

But the more sentimental view of houses in a place like Britain has its own history, embedded in a wider configuration of attitudes to the modern world. As I’ve touched on previously in relation to the history of the kitchen, the domestic sphere has always had a fraught relationship with modern industry and technology. During the industrial revolution, as the public realm of work became increasingly competitive and mechanised, the middle-class home came to be conceived as a sanctuary, an elaborately styled “palace of illusions” as Adrian Forty calls it, bathing its residents in an atmosphere of stability, respectability and continuity with the past. This is why, for instance, in the mid-nineteenth century, the American company Singer struggled to sell domestic sewing machines until it disguised them as traditional items of furniture. Wireless radio sets were still being concealed in this way during the 1940s.

This dialectic of modernity and tradition, with its accompanying class dynamics, has continued to shape expectations of the home. When technology did begin to show itself in the 1920s and 30s, it was largely confined to the bathroom and kitchen, which were sectioned off as functional areas of the house. At the same time, the arrival of architectural Modernism, whose geometric volumes proudly announced an allegiance to technology, efficiency and standardisation, presented a new threat for the home to be defined against. For much of the twentieth century, in Britain at least, a quiet conflict raged between two opposing visions of residential building. The architects and municipal authorities demanded Modernism, and were increasingly able to impose it on the working classes through the design of social housing. But this only deepened the attachment of sections of the middle-class to traditional styles, preferably in a suburb where there was room to carve out a modest sense of individuality.

In their fantastic study Dunroamin: The Suburban Semi and its Enemies, Paul Oliver, Ian Davis and Ian Bentley describe the formation of this suburban consciousness during the 1930s. It was not afraid of change as such; rather, nostalgic elements such as “Tudor beams and leaded lights,” invoking “linkages with a distant and splendid English past,” were part of a delicate balance between the old and the new, between the warmth of memory and the convenience of modern technology. Davis identifies the Dunroamin “spirit of ambiguity” as follows:

the desire for strong anchorage with the distant past in the buildings’ style, whilst wanting (at least in the bathroom or kitchen) all the latest and progressive ideas in planning or labour-saving appliances; the need for a cosy, warm, inward-looking house with oak beams and brick fireplaces… a concern to express the owner’s individuality in his home whilst still recognising that it was part of a street or community; the ambition to own a house that gave an unmistakable appearance of affluence, but at a minimum cost to the purchaser.

This captures remarkably well the responses to prefab I heard while reporting my recent Unherd piece. The people I spoke to were open to houses being constructed in a different way, but still wanted them to meet their existing criteria: to be reliable, durable, comfortable and affordable. IKEA’s modular homes – that’s right, these are literally flat-pack houses – are no more “modern” looking than the standard new-build today. They have clearly been designed to look and feel like familiar, semi-detached dwellings with gabled roofs and walls faced in artificial brick.

In other words, if prefab succeeds, it won’t be because people suddenly want to “roam home to a dome,” as Buckminster Fuller imagined. It will be because a new technology has successfully disguised itself as a conventional house. But perhaps such continuity in our notions of home, and the sense of security it provides, makes change in other areas of life easier to accept.

Nicely done, as was the Unherd piece.

As you probably know, in the US, manufactured home tends to be "mobile" (not actually mobile) homes, which are often expensive but seen, strongly, as underclass. "Trailer park" carries profound negative connotations in the middle class mind, fears of decline, maybe mental collapse, and sometimes hopes for escape, floating in the collective imagination somewhere above homelessness. At the same time, the problem of housing people has become acute in many parts of the country -- mass immigration, mass mental health, mass drugs, miscellaneous forms of precarity. So we are trying to build housing of this or that sort, and . . .

I think "refuge from modernity" is right, but you might go much further with this idea. Modernity, unfortunately, is a perennially difficult idea, but one thing it tends to be (and maybe all it really is), is a departure from the established. Every era has its "modern." (Mark Maguire and I discuss conceptions of the modern in Getting Through Security, which might be useful.). But home, at least in the middle class mind, is where one is, it identifies a person, not least legally. And home is where one hopes to live a long time, abide. So the idea of home devoted to replacement, abandonment, is a bit of a non-sequitur. Humans do not always think like that, of course. We might live in hotels, for example, or amongst properties and aristocratic kin, or perhaps be Japanese, or nomadic. But those would be different kinds of lives with different psychologies, as you suggest, anchored otherwise (or not, terrifyingly, and I've got homelessness on the brain). Anyway, keep up the good work.