It sounds like a book-lover’s dream: a library containing all the works ever written, all the works that could be written. Imagining such a paradise would have been far too dull for Jorge Louis Borges, the Argentine master of short stories. Instead, Borges turned the idea into a nightmare: a Library of Babel, as described in his 1941 story of that name.

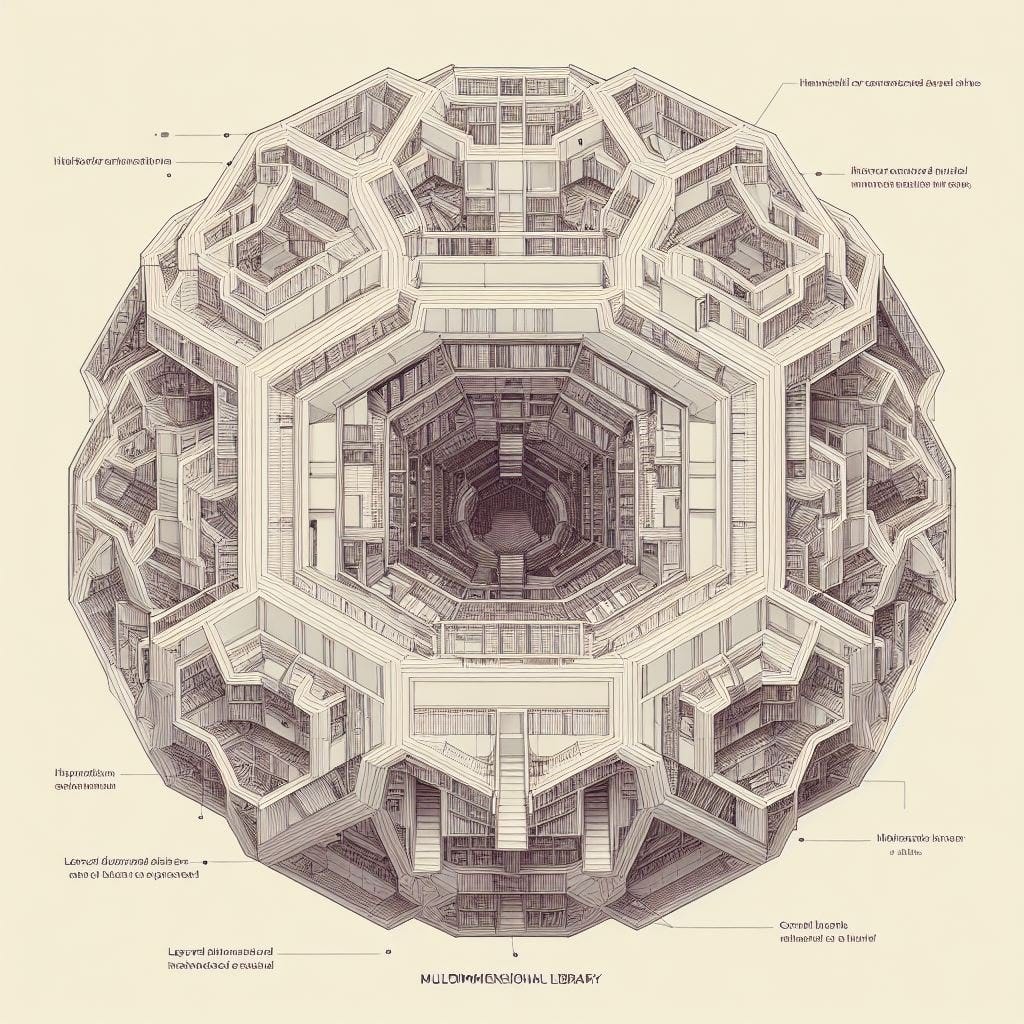

Few spaces, real or unreal, have matched the imaginative power of Borges’ library. It consists of “an indefinite and perhaps infinite number of hexagonal galleries,” and within these galleries are books containing every possible sequence of letters, spaces, commas and full stops. So it does, indeed, contain every book that could be written, but what that means in practice is an unimaginably vast body of random alphabetic characters and punctuation marks.

According to the narrator, who is a librarian (like everyone else in the story, for the library is their universe), the books are arranged as follows:

There are five shelves for each of the hexagon’s walls; each shelf contains thirty-five books of uniform format; each book is of four hundred and ten pages; each page, of forty lines, each line, of some eighty letters which are black in colour.

Following these specifications, the library is not actually infinite, but it does contain far more books than the number of atoms in our own universe. (If you want a more exact value, imagine a two followed by 1.8 million zeros).

The fable has delighted semantic theorists as well as mathematicians. Some have argued there is no actual information in the library, since anything which happens to be comprehensible is so only by coincidence. Others have latched onto the narrator’s insistence that, in fact, the library contains “not a single example of absolute nonsense,” for somewhere on its shelves it has invented the language needed to make any given sequence of characters meaningful. The philosopher W.V. Quine claimed the entire library could be reduced to just a single dot and a single dash – or in digital terms, a one and a zero – since anything can be expressed in binary notation.

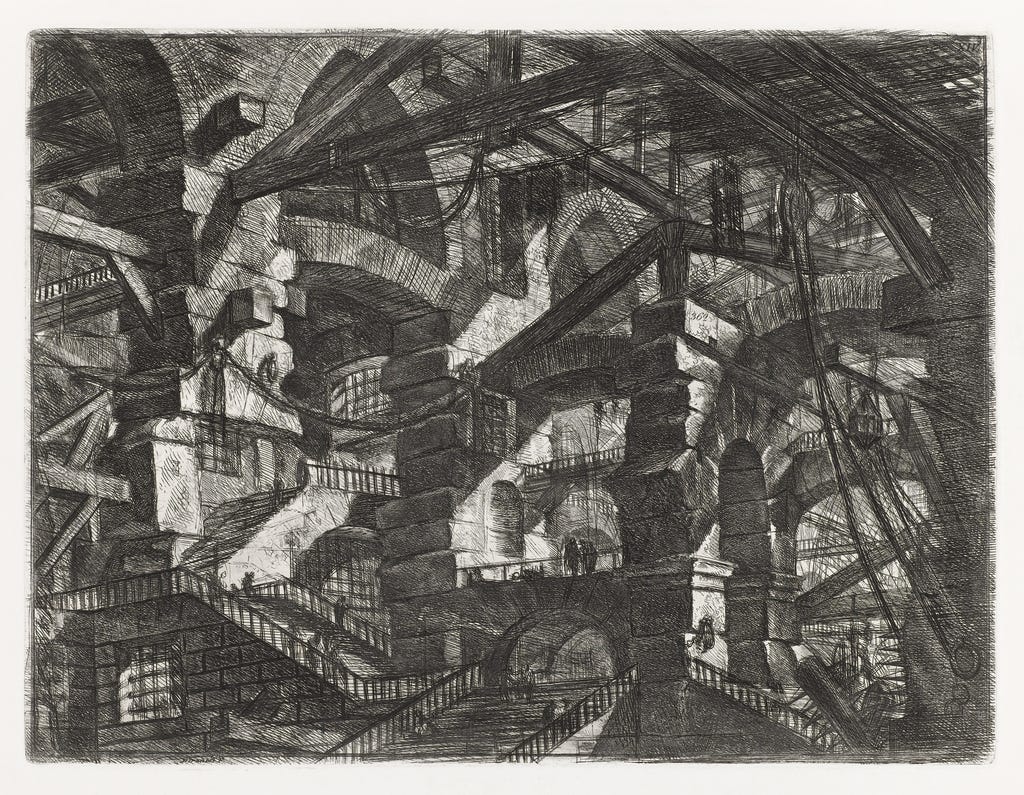

Yet Borges’ library is not just a thought experiment; it is the setting for an ill-fated society. His narrator speaks to us from a disastrous moment in the librarians’ history, when their civilisation is wracked by religious conflicts, fanaticism, destructive migrations and an epidemic of suicide. They have apparently been driven to despair by the realisation that, while the library must contain the answer to any and every problem, those answers are impossible to find in the mass of unintelligible text. As the narrator explains: “The certitude that some shelf in some hexagon held precious books and that these precious books were inaccessible, seemed almost intolerable.” (There is now a digital version of the library, created by the writer and programmer Jonathan Basile, so you can see for yourself the difficulty of finding even a single recognisable word).

The plight of the librarians begs to be read as some kind of allegory about our own doomed efforts to make sense of our cosmos. But it could also be seen more narrowly as a parody of modern notions of rationality and efficiency. This becomes apparent when we pay closer attention not to the contents of the library, but its physical form – its architecture.

Borges was famously obsessed with labyrinths, convoluted spaces of ambiguity and paradox. But the Library of Babel is a special kind of labyrinth. As we have seen, its structure is absolutely uniform, standardised and modular, consisting of identical hexagonal galleries with an equal distribution of shelves and books. As such, it recalls the rigid order of modern industrial and bureaucratic organisation. Hexagons are most closely associated with the honeycomb pattern of beehives, a longstanding symbol of impersonal and regimented social structures. With its endless repetition of these geometric cells, the library mimics the basic principle of mass production, where standardisation enables products to be churned out at low cost and enormous scale. (As the Romans observed centuries ago, hexagonal construction allows a highly economical use of resources).

Borges was a critic of functionalist architecture, the strand of Modernism which applied a similar logic of efficiency to buildings. In his later work The Chronicles of Bustos Domecq, co-authored with Adolfo Bioy-Casares, Borges skewers functionalism for placing its own obsession with simplicity and purity above the real needs of people. Considering Le Corbusier’s famous definition of the home as “a machine for living,” the narrator quips that it “seems less applicable to the Taj Mahal than to an oak tree or to a fish.” Or a beehive, we could add.

Borges’ library is itself a kind of satire of functionalism, not just in its stifling regularity but also in its meagre utilitarianism. We are told that in each of the narrow hallways connecting the galleries, there are “two very small closets,” one being a toilet and the other a place to sleep standing up. Such are the home comforts provided by the architects of Babel. We might also recall one of Jane Jacobs’ criticisms of top-down urban planning, that too much order can make a place disorientating. If everything looks the same, you can’t work out where you are. Like a giant car park or shopping mall, the library is so perfectly uniform that its inhabitants would be unable to situate themselves, let alone feel at home.

These conditions would be reason enough for the librarians to feel depressed, but their predicament goes deeper. In the structure of its rooms as well as the exhaustiveness of its contents, the library is evidently a planned, organised, highly functional space; but what then is its function? This is what the librarians tear themselves apart trying to work out. Their existential crisis stems not just from their failure to discover the ultimate meaning of the library, but from its absurd combination of extreme order and apparent meaninglessness, its systematic character devoid of clear purpose.

This resonates, of course, with many dystopian portrayals of modern society in the 20th century, especially those aimed at large organisations whose internal processes become divorced from their supposed aims. Borges’ library is like the bureaucratic workplace where the operations are as rigorous and methodical as they are pointless, where rational procedure becomes the essence of an irrational endeavour. Such situations are often described as Kafkaesque, and in fact, Borges admitted that with the Library of Babel, “I tried to be Kafka.”

So Borges’ famous story does not only present us with a palace of the mind. It invokes, in exaggerated form, certain aspects of modern design, illustrating the absurdity of a world where efficiency often seems to be an end in itself.

Love this article. I was dismantling a beehive two days ago and now seeing the experience in a totally different light. I can confirm that it looks pretty similar to what Borges describes.

Your point about the library being obviously designed was very insightful; I'd never thought of it like that before. Thanks!