In Kenneth Clark’s brilliant TV series Civilisation, first broadcast in 1969, there is an unintentionally poignant passage about London. Clark is in Greenwich, surveying the gorgeous baroque hospital there, and admiring some seventeenth-century astronomical instruments at the Royal Observatory. In his assessment – delivered, as always, with a wry hint of a smile, a flash of bad dentistry – there is a dark side to these elegant spaces and objects. They marked the birth of a “rational philosophy” that, in the course of time, “resulted in a new form of barbarism.” Here the camera pans across the surrounding cityscape: behold, “the squalid disorder of industrial society.”

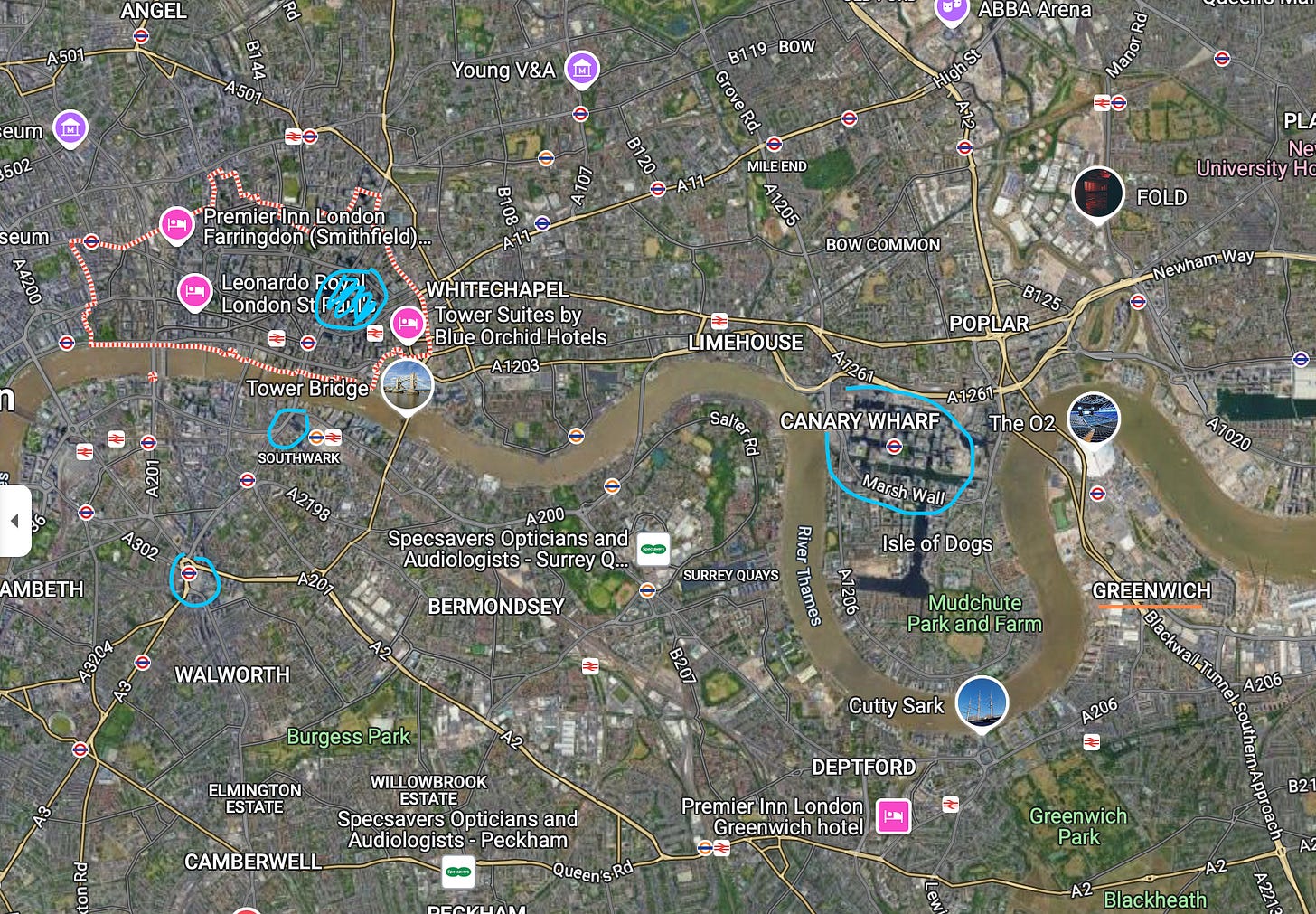

Except that, from the perspective of the 2020s, the skyline Clark expects us to recoil from actually appears rather quaint. The reason is that London had barely any skyscrapers at that time – St Paul’s Cathedral was its tallest building until 1963 – whereas looking west from Greenwich today, skyscrapers are practically all you can see. Just across the river is the Isle of Dogs, where in the 1980s and 90s the decaying industrial docklands were redeveloped into Canary Wharf, a major centre of global finance. Beyond this thicket of glass stands the enormous Shard and the City of London – aka the Square Mile, London’s original financial district – where another high-rise cluster has sprouted, especially in the last three decades. Less noticeable from here, if only for the distance, are the soaring towers of luxury apartments that hug the Thames as it makes its southwards bend into Lambeth.

I was reflecting on all this last month when I wrote a short piece about 1 Undershaft, a new skyscraper which has just been approved in the Square Mile. At 309.6 metres, it will match the Shard as London’s tallest building, and these two soaring edifices will stare at each other across the river like Mordor and Isengard in Tolkien’s Two Towers. This, I said, was only the latest outcome of processes which have long been “destroying the city’s character and replacing it with a global real-estate market of anonymous glass and steel.” It’s worth unpacking this claim a little. Speaking about character in this way risks sounding, at best, naively sentimental, and at worst self-indulgently pessimistic. Character is an ambiguous phenomenon, especially in a modern city, which tends to encompass radically different perspectives and to be changing all the time. As Clark’s distaste for an earlier London suggests, character may have a ghostly tendency to be always slipping into the past.

But if ambiguity, contingency and subjectivity can make character difficult to pin down, they don’t make it any less important or worthy of attention.

I left London two years ago, after living there for over a decade. For much of that time, I didn’t even notice that tall glass was metastasising in the city, assuming that such buildings were in some sense natural to the urban world. If anything drew my attention to them, it was their spectral beauty. I once rode the Docklands Light Railway through Canary Wharf on one of those days when cities dissolve into rain and mist. It was and remains one of my most transcendent experiences of urban space. The railway, raised above street level, seemed to be floating on the air as it threaded its course among skyscrapers that rose suddenly from the swirling white atmosphere, like the structures of some hallucinated Atlantis. Years later, I found the same ethereal quality in the glass skyscrapers imagined by Mies van der Rohe in the early 1920s; romantic edifices of the mind, conceived decades before he managed to get one built.

Some aspects of a city’s character are immediately visible, others are learned gradually over time. We learn from experience, conversation, accounts of the past. Character becomes most apparent when we gain or lose it, by moving to a new area or seeing our familiar surroundings transformed by some soulless redevelopment. For some of us, character consciousness comes with a new suspicion towards the past. How did the city change before we knew it? How was character created, and how squandered?

To my mind, character is about particularity, and the sense of harmony associated with feeling at home or positively connected with one’s surroundings. It is a kind of genius loci, a spirit of place, which arises from its various natural and manmade elements, and from the rhythms of life they support. Materials, spatial patterns and building styles all contribute to character, especially when they are aesthetically distinctive, or provide a connection with earlier generations of inhabitants. (For modern cities as for prehistoric settlements, spirit of place owes a lot to the spirits of the dead).

This is not the time to discuss all of the ways that characterful places can bring contentment, reward attention, nourish curiosity. The important point is that we generally respond to, and connect with, places that feel like somewhere rather than anywhere. As with people, the character of a place is part of its identity and its quiddity, and much of the beauty of character lies ultimately in that mysterious sense of a thing being what it, specifically, is.

As I’ve acknowledged, tall glass can be aesthetically sublime. There are also cases – Euston Tower, for instance – where it works quite nicely with London’s older building styles, thanks to sympathetic design and placement. But these are exceptions. The case against tall glass begins with the fact that, in a city like London, it has a homogenising effect. It is a largely generic type of building – it could be almost anywhere – and therefore doesn’t contribute to a sense of place. More importantly, it overshadows and outshines other elements in the city that are distinctive.

London is not like New York, a metropolis with a stylistically rich heritage of skyscrapers going back a century. Nor is it like Dubai, a blank slate for capitalist fantasy. Until quite recently, London was essentially a low- and medium-rise city, faced in brick, stone and occasionally concrete, its skyline punctuated by church spires and, as Kenneth Clark reminds us, factory chimneys. Many new styles can, and have, accommodate themselves to these parameters. But tall glass is not like other styles, since it dominates the cityscape – dominates the horizon with its silhouettes, and the street level with its slick, liquidating surfaces.

The result – to borrow a term from the architect Thomas Heatherwick – is a “blandemic” of monotonous superstructures that offer little food for the soul, whether in form, scale, texture or detail. A growing portion of London could easily be mistaken for dozens of other cities around the world, even if a few of its more famous skyscrapers have funny shapes.

To a designer seeking the deeper springs and sources of character, the Square Mile offers an uncommon wealth of history. It is the ancient core of London, the point where the Romans first bridged the Thames almost 2,000 years ago, and still occupies its slightly chaotic Roman street plan. Its governing body, a guild known as the City of London Corporation, is almost 900 years old. It boasts 23 of Wren’s churches, built after the Great Fire. For almost a century, between the Napoleonic Wars and the First World War, it was the undisputed financial centre of the world; the first centre, in fact, to underpin a truly global financial system, for which the British Empire provided a framework. It also happens to have some of the best contemporary architecture in London, as I discovered over years of taking the 55 bus.

The curious thing about 1 Undershaft – the new mega-scraper slated for the Square Mile – is that its architect, Eric Parry, seems to grasp the importance of responding sensitively to a setting. That is the impression one gets from his 2015 pamphlet Context, and this excellent profile by Oliver Wainwright. Parry has even warned that tall glass will “transform and arguably overwhelm London.” And yet, his design for 1 Undershaft amounts to almost a quarter of a mile’s worth of vertically stacked glass cuboid, further bloating a group of skyscrapers that dominates the London skyline even from the opposite, western side of the city. It’s almost as though Parry’s real role is to legitimise the project with his experience and expertise. And that, in fairness, would only be in keeping with architecture’s relationship to tall glass more generally.

As Brian Potter emphasises in a recent post, the spread of glass skyscrapers has had very little to do with architects, and a lot to do with property developers and planning committees. Very tall structures make more money, because they squeeze lots of floor space onto a small stamp of land, and the glass box is cheap in terms of materials, design and construction. 1 Undershaft is being developed by Aroland Holdings, a Singaporean investment consortium that belongs to the owners of Wilmar International, the world’s biggest palm oil producer (which has, incidentally, faced numerous allegations of large-scale environmental and labour abuses). Tall glass also appeals to local politicians because it brings sizeable investments (including, let’s be honest, the kinds of investments which come in the proverbial brown envelopes), and boosts job and housing statistics. No doubt shiny, thrusting structures appeal to the vanity of some architects, but more important, again, is the vanity of those who rent the office spaces and residential units, and who provide the permissions.

So the midwives of tall glass in London were not architects, but men like Michael Cassidy, the former head of planning for the City of London Corporation. In a recent interview Cassidy boasts of how, in the 1980s, he deliberately rejected guidelines relating to character, which recommended, for instance, Portland stone and Edwardian proportions. “There was a draft City plan that was completely out of touch with what developers and occupiers wanted,” he claims. “So we set about demolishing it.” One way to view the financial services industry is as a small subculture which, thanks to its patronage of skyscrapers, has had an enormous impact on the character of cities around the world. Some will say, of course, that the tall glass in Canary Wharf and the Square Mile are a sign of London’s ongoing relevance as a major city, but one could also make a contrary case. Important though the financial sector undoubtedly is, Britain’s governing class has become ever more desperate to support it because our other industries – those smokestacks that unsettled Kenneth Clark – have withered away. The towers are a sign of weakness as well as strength.

As for that other manifestation of tall glass, the luxury apartment building, these don’t indicate London’s wealth so much as its attractiveness to wealthy people, and often corrupt ones at that. In 2017, for instance, Transparency International looked at 14 upmarket apartment buildings then under development in London, and found that almost 80 per cent of the units had been sold to foreign investors, of which half were buyers from “high corruption risk jurisdictions.” There is thus a strange correspondence between London’s most flashy buildings and its most traditional, since the latter also increasingly serve an international elite as settings for luxury retail and hospitality.

Such commercialisation of heritage is not very conducive to character either, but tall glass is especially corrosive because it so starkly embodies the social and economic pinciples behind its construction. Architecture concerned solely with exclusivity, or with maximising returns, or with the anonymous circulation of people and money, is unlikely to contribute much to the life and character of the city. Not all tall glass falls into these categories, but much of it does.

Having said all this, it still feels foolish to even expect character from a major urban centre. Such places are the nodal points of capitalism, seething epicentres of modernity, the sites of a vast and on-going experiment in human living, their physical and social fabric strained by the millions who gravitate towards them for overwhelmingly economic reasons. To seek enduring character here is like drawing up blueprints for a sandcastle. Or maybe we should say that transformation is part of London’s character. After all, the city’s size and form are essentially a legacy of industrialisation, when in a little over a century, between 1800-1911, its population septupled from 1 million to 7 million. Kenneth Clark’s later aesthetic qualms should not disguise how chaotic and squalid this process really was, as recorded by Dickens and other horrified observers. Big hub cities have their sheltered neighbourhoods, but they have remained places of upheaval ever since.

We also need to reckon with the human ability to feel affection and appreciation for almost any familiar place. People who live somewhere tend to experience it as having character, or something like character, even when an outsider sees none. In her introduction to JG Ballard’s great novel Crash, Zadie Smith remembers growing up in west London and “climbing brute concrete stairs – over four-lane roads – to reach the houses of friends, whose windows were often black with the grime of the A41.” Ballard portrays this world of asphalt and traffic as alienating to the point of dehumanisation, but for Smith it is “fond and familiar,” “sentimental,” “even beautiful.” Character is not quite relativistic, but since it is rooted in particularity, our understanding of it does need to remain malleable, aware of the many possibilities in human feeling and experience.

Maybe we should say that, in the modern era, London’s character has undergone waves of change, successive shatterings and reconstitutions, at times relatively stable and coherent before succumbing again to dramatic shifts. The 1930s saw housebuilding on a big scale, and the rise of the suburb as a distinctive middle class environment. After the Second World War came the era of social housing and Modernism. Tall glass belongs to a period when globalisation has taken the city in some respects back to its nineteenth-century phase of chaotic growth and inequality, attracting a disproportionate number of the world’s millionaires as well as an unprecedented influx of migrants from much poorer parts of the world. Even against this backdrop though, tall glass can be seen as destructive of the city’s previous character rather than just an evolution of it. The reason, aside from those I’ve already given, lies in its monumental nature. Once they reach a certain size and prominence, structures become, in effect, totems or idols, celebrating the power of the forces they represent, and demanding recognition from those who live in their shadow. This is a domain of symbolism with implications for the very essence of a city’s character.

Whatever the gods honoured by these shiny obelisks, my service to them is finished, the city’s metabolism having now ejected me as forcefully as it once sucked me in. I have traded tall glass for tall hills, and couldn’t be happier.

There is so much in this essay. It is worth being on Substack for. And will be worth reading again. Not least for the writing, which has (dare I say it) such character. Thank you.

I was also a 55 bus traveller, getting off at Liverpool St, unhappy and sometimes hungover in one direction, angrily unhappy on the return journey.

Rolling hills, intermittent, rather than tall ones, are the line of sight where I am now. The character of this kind of landscape surely endures.