“They as good as broke our public services.” Keir Starmer said this in a BBC interview a year ago, alluding to the dysfunction that had overtaken the rail system, the health service, and utilities such as water under the Conservative government. It was an obvious line of attack, and Labour continued using it through to this month’s election, and has not stopped using it since winning power. Nigel Farage adopted the same theme when he took the reins of the insurgent Reform Party in June – a move that turned the Conservative rout into a massacre, since Reform ended up taking fourteen percent of the national vote. Announcing his campaign in Clacton, Essex, Farage declared that “nothing in this country works anymore.”

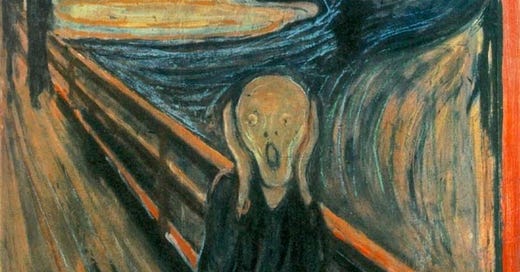

In a country with social democratic leanings like the U.K., public services are always going to be politically salient. Transport systems, schools, utility bills and (above all) hospital waiting lists are the arenas where we judge whether a government is fulfilling its contract with us, the people. From a design perspective, though, we might emphasise another, more visceral reason that public services can be so consequential. Using a system that does not work as it should – that is unreliable, badly planned, and unresponsive to our needs – generates deep feelings of frustration and anger. These emotional responses, which bring with them a deep desire to blame someone, can overwhelm a rational assessment of a government’s policies. Hence the plausibility of the old joke that Italians accepted Mussolini’s dictatorship because, whatever his faults, at least he made the trains run on time.

I tend to focus on design in relation to material artefacts, but there is a reason the field has expanded into less concrete realms: service design, systems design, “design thinking” and so on. We live in complex societies where life entails constant interaction with large, impersonal structures, from government agencies to corporations and technological systems. This is a recipe for alienation and resentment, but as David Westbrook has eloquently written, we ourselves are at least partly to blame. The modern, democratic worldview expects institutions to be accountable to the popular will, but also to provide benefits and opportunities of the kind that only distant, unaccountable bureaucracies can organise. From that contradiction emerges the unavoidable importance of design. To achieve a well-functioning modern society, there is ultimately no substitute for systems that are creatively, competently conceived by bureaucracies working in the public interest.

If we take these insights further, we might arrive at a different perspective on contemporary politics. Public services show us that the common experiences of citizens, the emotional texture of their daily lives, can shape their political sentiments. But why stop at these particular experiences? There is no reason to think that public services are the only case where people use democracy to punish someone for the dysfunction they encounter on a daily basis. For a decade, prompted by the rise of anti-establishment, “populist” movements, commentators have been trying to explain the dissatisfaction and anger in the western body politic. Perhaps they should pay closer attention to all of the obstacles and irritations with which everyday life is currently strewn.

They would notice that we have an economic model where, to put it bluntly, everything feels like a con. Many services, from essential apps to supermarket discount programmes, are obviously schemes to profit from collecting our data, but that is never admitted. To pretend they aren’t raising prices, companies instead reduce the size or quality of their products, hoping we won’t notice. (This practice, called shrinkflation, is now so widespread that politicians in the U.S., Europe and South Korea have condemned it). To squeeze more revenue out of their residents, local governments act like budget airlines, constantly inventing new fines and charges. As for public services, the problem in a country like Britain is not just that they are deteriorating, but that they are simultaneously becoming more expensive as the companies managing them take enormous profits.

Another source of frustration is the proliferation of rules that, while they may appear justifiable in their own terms, feel like arbitrary impositions to those on the receiving end. Reporting and travelling over the past year, I’ve heard no end of complaints about regulations and paperwork from fishermen, architects, farmers, professors and medical professionals, to name a few. It’s no coincidence that mandatory yellow vests for motorists and heat pumps for homeowners have become symbols of protest in France and Germany. Then there is the daily friction that arises from service providers forcing their customers to use tech that doesn’t work properly. The most exasperating example is still the replacement of customer service staff with badly functioning chatbots and webforms.

I could go on, but you get the point. In isolation, each of these issues is worth little more than an angry monologue at the pub. Taken together, they help to explain why one of the main political currents of recent years has been pissed off.

On the other hand, there now seems to be less room for the rather grand role I awarded design earlier. Many of these mundane agonies – public services included – are not simply failures of user experience, but can be traced back to more structural factors. Aligning the interests of bureaucracies with those of the public is easier said than done. Much of the dysfunction we see around us stems from the ownership of major assets (including houses, hospitals, schools, energy infrastructure and transport systems) by firms geared towards rent-seeking and short-term profit. This trend has been analysed by the economic geographer Brett Christophers. In his excellent introduction to Christophers’ work, Dan Hitchens describes a financial model based on “a steady transfer of ownership and control away from the citizen, the consumer, the employee, the community, and the democratically elected government, toward institutions whose workings are often invisible to public view.”

But none of this contradicts the importance of design for the systems we rely on. It merely shows that certain conditions are necessary for design to be given the weight it is due. I once spoke to a mechanic who complained about the declining standard of car making, remarking that “they used to be designed by engineers, now they’re designed by accountants.” He was acknowledging a conflict between the imperatives of design and the institutions that employ designers. Inherent to design – or good design, at least – is a concern for quality and for the end user’s experience. One goal of a modern politics should be to create space for such ideals to be enacted.

Cheap, fast, good - choose two, they said.

But unfortunately you can only choose one and the British chose cheap.

Wessie, thanks for the shout-out! As I've said, you're onto something really important. It's a little to easier to say "bureaucracy" or "capitalism." Cars may be built by accountants, one might say, but Ford and Daimler were businesses from the beginning. Let me suggest that early modernism relied upon a craft tradition (your piece on house building) that the 20th century did not really sustain, indeed struggled against in the name of democracy. So if social position is determined by job, and jobs are in principle open . . . symbol manipulation rises up the ladder. So you might not want to run a plumbing supply company in St Louis, but maybe you join a private equity firm that . . . runs a plumbing supply company. Thus what we might think of as the abstraction, and distance from the physical, and so the shoddiness of the material, stems from democratization itself. Maybe. Probably needs more thought. Again, keep up the great work.